On Nov. 2, English broadcaster David Attenborough, opened the World Leaders Summit on Climate Change with a

speech that still gives me goosebumps. “We are already in trouble,” he says. “The stability we all depend on is breaking. This story is one of inequality as well as instability. Today, those who’ve done the least to cause this problem are being the hardest hit.”

I see this reality as I talk to moms in my community here in Canada and as I look at the impact in Sub-Saharan Africa, the home I knew for most of my childhood. Across the globe, countries and communities who contribute the least to greenhouse gas emissions are disproportionately bearing the burden of negative impact. For example, in 2018,

Madagascar contributed just 0.06 per cent of global Green House Gas emissions, yet it is currently facing what could be the world’s first famine in modern history caused by climate change, with food insecurity affecting an estimated 1.14 million people in the country.

Across the globe, food production is becoming unreliable and the most vulnerable are being left behind in a race to adapt and survive.

As a result of climate variability, particularly temperature increases and rainfall variability, agricultural production is facing an unprecedented challenge to meet the needs of a growing global population.

In Canada, c

hallenges with droughts, unpredictable crops yields and heat-waves which threaten livestock, among other things, are driving an ever-increasing rise in food prices.

Canada’s Food Price Report for 2021 predicted an overall food price increase of three to five per cent, with climate change listed as a ‘very significant’ driver of this increase. The

HungerCount 2021 Report points to the alarming reality that food bank visits have increased by over 20 per cent since 2019. And sadly, more than one-third of the clients are children and close to 20 per cent are single-parent households. Clearly the impact is being felt unequally.

In Tanzania, a man moves his livestock across an arid landscape. Food and water for livestock, crucial to family livelihoods, is becoming harder to find due to climate change.

In Tanzania, a man moves his livestock across an arid landscape. Food and water for livestock, crucial to family livelihoods, is becoming harder to find due to climate change.

In low-income countries, when food production becomes unreliable, it can become impossible to find the resources to fill the gaps. Lack of action is putting lives at risk.

So, as the UN Climate Change Conference closes,

World Vision is warning that failed negotiations could push millions more towards starvation.

There are now 45 million people worldwide who are at extreme risk of famine, a staggering 300 per cent increase during the past six months – largely due to the multiplier effects of conflict, COVID-19 and climate change. In 2020, nearly one in three people in the world (2.37 billion) did not have access to adequate food – an increase of almost 320 million people in just one year!

This is also reflected in rising levels of malnutrition – with 149.2 million children under five years of age affected by stunting and 45.4 million suffering from wasting.

Recent projections also indicate that the malnutrition crises could result in an additional 250 child deaths

per day – this will translate to an additional 283,000 child deaths over three years if we don’t act fast.

The climate crisis is a story of inequality – where those with less power face the most serious consequences. For women and girls, gendered roles often mean they feel the effects of climate shocks most acutely as they are responsible for producing and preparing food, collecting water and wood for heating and cooking – all tasks that rely heavily on natural resources.

As the effects of climate change challenge agricultural production, deplete food supplies and damage livestock, people are turning to more desperate solutions for sustenance, often at the expense of food quality and women and girls’ safety. For women and girls who already eat last, least and poorer quality food, this deprivation of essential nutrients at critical points in their life, combined with the risk for gender-based violence and early marriage, can mean life-long consequences to their ability to live a healthy, active, and prosperous life.

And yet they have little to no say in climate change plans. Their voices are often absent or stifled at the table when climate change mitigation policies and plans are made, creating a critical gap in developing solutions for more equitable and sustainable actions to address climate change. This gender inequality is shockingly apparent in the

lack of female decision makers at COP26.

Critical to solving the climate crisis is the leadership and empowerment of women

But there is hope. There is considerable evidence that women can be powerful change agents and can play a crucial role in climate change adaptation and mitigation. Across the globe,

women are standing up and blazing a path for a better future with gender-transformative climate resilient measures – ensuring that their families and generations to come will have access to healthy food.

Women like 44-year-old Pamela from Kenya’s Migori County.

Pamela is among the many residents of her community who previously suffered from the adverse effects of floods. The seasonal floods, wreaked havoc in her village, were attributed to human deforestation activities. This led to changing weather patterns in the area. Residents started experiencing long seasons of drought and short seasons of rainfall that were accompanied by devastating floods due to the bare land – devoid of trees and other vegetation.

Pamela has become a fierce advocate for Farmer-Managed Natural Regeneration in her Kenyan community.

Pamela has become a fierce advocate for Farmer-Managed Natural Regeneration in her Kenyan community.

Being a widow and a smallholder farmer, Pamela notes that she would suffer huge setbacks during rainy seasons as a result of the floods.

“My husband, who was the breadwinner in my family, died in 2008, leaving me with five children. Each year, we would be displaced by floods, which made life difficult. The crops I used to grow on my small piece of land would always be destroyed – either by floods or drought. As a result, providing for my family became a burden,” says Pamela.

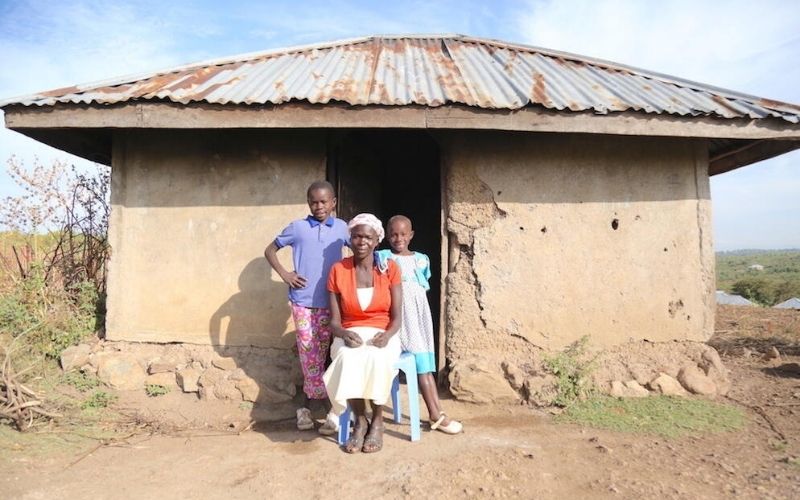

Pamela sits with her children in front of their house.

Pamela sits with her children in front of their house.

The tides began changing for her community, when World Vision started promoting afforestation initiatives through its Regreening Africa project, funded by the European Union.

“The project enlightened us on the importance of environmental conservation. We learnt that trees play a key role in preventing rainwater runoff which causes floods. The sensitization made us see the connection between our destructive environmental practices and the flood problems that had been affecting us for many years,” notes Pamela.

To revive these valuable indigenous trees, Pamela and other community members are using a low-cost tree growth management technique known as the Farmer Managed Natural Regeneration (FMNR) approach that World Vision has been promoting in the area.

“This allows us to use naturally occurring tree seeds in the soil, as well as tree stumps which we manage effectively through pruning and protection from destructive animals so as to promote the regrowth of the indigenous trees,” she says.

This epiphany inspired Pamela to become an environmental conservation champion and advocate for the formation of the Mirema Forest Association, which has been spearheading effective tree planting, revival and management approaches with the aim of restoring the forest and fighting biodiversity loss.

Pamela passes on her knowledge of FMNR and love for the environment to her children.

Pamela passes on her knowledge of FMNR and love for the environment to her children.

Their efforts have paid off. In about four years, Pamela and her dedicated community members were able to ‘regenerate the bare land with indigenous trees as well as other new varieties of tree species.

For Pamela’s community, it means the area now receives adequate rainfall. For Pamela it means she can ensure her family has nutritious food to eat. Pamela’s strong leadership and powerful actions are paving the way to sustainably improve nutrition and access to affordable healthy diets for her entire community.

We need to catalyze more of these transformative efforts – with women at the helm! The

recent announcement by the Government of Canada to allocate 20 per cent of the climate finance commitment to nature-based solutions in developing countries is a step in the right direction. World leaders need to follow with bold commitments on climate action and to stop the hunger crisis.