Afghanistan’s humanitarian disaster is staggering in both scope and scale. By early 2022, more than half the country’s people –

24.4 million in total – were in dire need.

Ninety-five per cent of all Afghans lacked enough to eat, with women and children most cruelly affected.

What is happening in Afghanistan to cause this?

The situation became still more complex after the

Taliban became Afghanistan’s de facto authority in August 2021. Significant amounts of Western aid to Afghanistan abruptly ceased.

Within months, more than half of Afghanistan’s children under five were confronting acute malnutrition. At least

one million faced the threat of death as a result.

“The current humanitarian crisis

could kill far more Afghans than the past 20 years of war,” David Miliband, president of the International Rescue Committee, said in February 2022.

In this article, we’ll unpack the crisis in Afghanistan. We’ll explore implications for the country’s people unless assistance arrives with all possible speed. And we’ll tell you why Canadians aren’t yet able to help.

Afghanistan: hope vs. hunger

Up to

97 per cent of people in Afghanistan don’t have enough to eat. By 2022, the country was ranking a global first for the number of people facing emergency food insecurity –

up 35 per cent in a year.

In Canada, the news from Afghanistan is heartbreaking and deeply disturbing. Food is top priority for every Afghan. Each month, more children cry out from the ravaging hunger before sinking into the listlessness of severe acute malnutrition.

A small child receives vaccinations and care for malnutrition, at a World Vision mobile clinic in November 2021. Photo: World Vision Afghanistan. Please note, for the safety of Afghan civilians and our staff, we won’t show full faces in this article.

A small child receives vaccinations and care for malnutrition, at a World Vision mobile clinic in November 2021. Photo: World Vision Afghanistan. Please note, for the safety of Afghan civilians and our staff, we won’t show full faces in this article.

Today, economic and banking systems are in a state of collapse. Millions of Afghans have lost their livelihoods. And outside of major cities, major services are often simply unavailable.

Afghanistan’s need has become devastating. So has Afghans’ pain, shared UN Secretary-General António Guterres in a

January 2022 media briefing on Afghanistan.

“Babies being sold to feed their siblings” he said, of very young girls forced into marriage contracts. “Freezing health facilities overflowing with malnourished children. People burning their possessions to keep warm.”

The signs of an impending humanitarian crisis grew more pronounced each day, starting in September 2021.

The country had recently transitioned to a de facto authority (the Taliban) after decades of propping-up by international donors.

Photo: World Vision Afghanistan Staff

Photo: World Vision Afghanistan Staff

“After decades of war, suffering and insecurity [Afghanistan’s people] face perhaps their most perilous hour,”

reported the United Nations that month. Even then, one in three

Afghans did not know where they would get their next meal.

And, as chaos increased in the country, winter was coming on fast. “I’m very afraid … this winter will be even worse than we can imagine,” one 40-year-old Afghan woman told the

New York Times.

In rural and urban areas alike, millions of people were facing the reality that their children might not survive the cold months.

As Afghanistan’s harsh winter set in, many families were making the impossible choice between food and warmth. Photo: Ralph Baydoun

The fallacy of ‘choice’ in Afghanistan

As Afghanistan’s harsh winter set in, many families were making the impossible choice between food and warmth. Photo: Ralph Baydoun

The fallacy of ‘choice’ in Afghanistan

By January 2022, in the thick of winter, millions of Afghan families were choosing between food and warmth. For parents and caregivers, the terrible choices only began there.

“Our teams have told us of families selling their youngest daughters for future marriage in return for advance payment,” said World Vision Canada’s President Michael Messenger. He was speaking to the House of Commons Special Committee on Afghanistan in January 2022.

Really, these aren’t choices or decisions – not in the sense that many Canadians experience them. They are extreme coping strategies. Afghan families are trying to keep the greatest number of children alive for the longest period of time.

Afghanistan was already one of the most dangerous places to be a child. But by February 2022, the degree of suffering was virtually unprecedented. Photo: World Vision Afghanistan Staff

What has caused Afghanistan’s humanitarian crisis?

Afghanistan was already one of the most dangerous places to be a child. But by February 2022, the degree of suffering was virtually unprecedented. Photo: World Vision Afghanistan Staff

What has caused Afghanistan’s humanitarian crisis?

Afghanistan’s people are contending with many emergencies simultaneously,

as outlined in a 2022 report from the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs.

Together, these threats have caused a full-blown humanitarian disaster that’s both naturally occurring and man-made. Afghanistan is experiencing:

- The worst drought in 27 years (the second in just four years), threatening the livelihood of millions of people in 25 of the country’s 34 provinces.

- The effects of an already over-burdened health system straining to survive shocks like COVID-19, spikes in waterborne diseases and persistent strains of polio.

- The sudden collapse in predictable funding (from international donors) that had kept the nationwide health infrastructure afloat.

- A dire situation for women and girls, with barriers to accessing healthcare and education. Several policies curtail women’s freedom of movement, expression and association. Many are deprived of the ability to earning an income.

- An economic crisis that has sent prices skyrocketing, while simultaneously diminishing people’s purchasing power.

- Increasing desperation, as families take on unmanageable debt burdens and rely on dangerous coping measures to survive (e.g., child labour and child marriage).

Childhood under siege in Afghanistan

For many years,

child and maternal mortality rates in Afghanistan have been amoung the highest in the world. Now, there’s a withering drought to contend with as well as catastrophic economic collapse.

Babies the youngest victims

Within months of Afghanistan’s regime change,

hospital wards filled up with premature babies facing death. Even then, staff (and other civil servants)

were going unpaid. Medication and supplies were running dangerously low.

This photo was taken in November 2021, in a clinic for children with severe illness. Across the country, supplies such as antibiotics for IV bags are running low. Photo: World Vision Afghanistan

This photo was taken in November 2021, in a clinic for children with severe illness. Across the country, supplies such as antibiotics for IV bags are running low. Photo: World Vision Afghanistan

When healthcare systems crumble, children are the youngest victims. The younger the child, the more vulnerable to illness, malnutrition, neglect and abuse. Newborns are at greatest risk of all,

many malnourished even before birth.

Begging for survival

Older Afghan children (though some just kindergarten-age) are engaged in

various forms of labour. Scared, hungry and cold, children in cities work long hours, trying to sell found items like plastic bags.

See a photo essay in The Guardian.

“Now there is no job for my father to do and bring food home,” one 12-year-old girl told

The Guardian. “One day we have food and the next day we don’t.”

Photo: World Vision Afghanistan

Photo: World Vision Afghanistan

For millions of Afghan families, hunger is a constant.

Food prices have skyrocketed since August 2021, with wheat prices increasing 50 per cent.

Half of children under five are expected to suffer from

acute malnutrition said UNICEF in October 2021.

In remote regions, thousands of internally displaced families are battling to survive the harsh winter, without food, medical care adequate shelter. Of the 700,000 forcibly displaced by recent conflict,

80 per cent were women and children.

Battling illness in Afghanistan

Even before the regime change,

millions of Afghan children were dying each year from preventable illnesses like pneumonia and diarrhea. Malnutrition, as well as lack of clean water, safe sanitation and healthcare, left babies and young children at greatest risk.

With the events of late 2021, major outbreaks of life-threatening diseases begun impacting more children. By December 2021, the UN reported:

In Canada, such illnesses would be prevented or quickly treated with health care and information, as well as vaccines, clean water and safe sanitation.

Children may share water sources with animals who defecate while they drink, contaminating the water. Waterborne illnesses can kill children or cause ongoing diarrhea and dehydration. Photo: World Vision Afghanistan

Children may share water sources with animals who defecate while they drink, contaminating the water. Waterborne illnesses can kill children or cause ongoing diarrhea and dehydration. Photo: World Vision Afghanistan

But in Afghanistan and around the world, the effects of illness and malnutrition

can last a lifetime. Malnourished children often remain stunted – both physically and mentally – for the rest of their days.

Illness and malnutrition today can leave Afghanistan’s children struggling to learn in the future, or succeed in a job, or support any children they have.

Education in peril in Afghanistan

“What is at stake in Afghanistan is the absolute necessity of preserving the gains made in education, especially for girls … “

Audrey Azoulay, director general of UNESCO

Every child in the world

has the right to go to school. Yet for generations, millions of Afghanistan’s children have had little or no access to consistent, quality learning.

Schools are

few and far between, especially in the poorest, most remote regions. Trained, paid teachers – especially women – are equally scarce. Armed conflict and economic crisis have contributed to the lack of a strong education system, as have COVID-19 safety measures.

For cultural reasons,

girls in Afghanistan have struggled disproportionately to access education. Yet a 2021 UNESCO report described how

learning for girls had been starting to improve. For example:

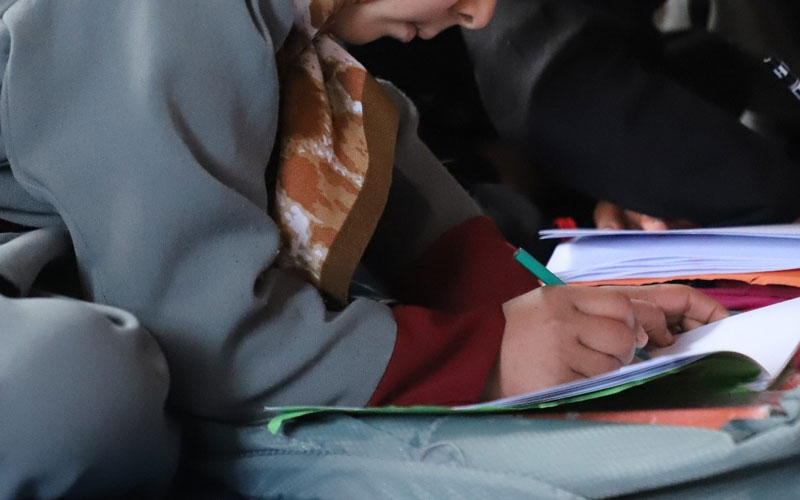

This six-year-old girl was too young for school but determined to learn. World Vision invited her to one of our learning centres in 2021, before political shifts in Afghanistan. Photo: World Vision Afghanistan.

This six-year-old girl was too young for school but determined to learn. World Vision invited her to one of our learning centres in 2021, before political shifts in Afghanistan. Photo: World Vision Afghanistan.

Recently, education in Afghanistan has been under great strain – especially for girls.

The COVID-19 pandemic, ongoing conflict, and

changes under the de facto authority have all contributed.

Girls banned from high school

After the de facto authority (Taliban) assumed power in August 2021, decisions around education have been increasingly hard to predict.

Since the regime changed,

girls have been banned from education beyond middle school in most of the country. The decision to allow them to return in March 2022

was reversed at the last minute.

“Education was the only way to give us some hope in these times of despair,” one 15-year-old Afghan girl told a

New York Times reporter. “It was the only right we hoped for, and it has been taken away.”

“Beyond their equal right to education, [the denial of education] leaves [girls] more exposed to violence, poverty and exploitation,” said Michelle Bachelet, the UN human rights high commissioner.

World Vision is advocating for the following for all of Afghanistan’s children:

- The guarantee of continuity of education for all girls, boys and young people in Afghanistan – including those from ethnic and religious minorities.

- Immediate measures to minimize disruption caused by political instability or by the lasting impact of COVID-19 pandemic or the ongoing hunger crisis.

- Ensuring that male and female educators and administrators are able to safely play their roles to facilitate the education of all children and youth.

- Development of a long-term plan for safe and inclusive quality education for all.

World Vision notes that co-ordinated international support and predictable aid will also be needed, for education to survive and thrive in Afghanistan.

In recent months, the international community has made girls’ education a central condition of foreign aid. Without it, the humanitarian crisis in Afghanistan may worsen still further.

An altered photograph from 2020 of a 12-year-old girl in Afghanistan (left) and her 24-year-old mother. The family chose not to marry off their daughter, with the help of community education. Picture: World Vision Afghanistan staff

Limit women, hurt their children

An altered photograph from 2020 of a 12-year-old girl in Afghanistan (left) and her 24-year-old mother. The family chose not to marry off their daughter, with the help of community education. Picture: World Vision Afghanistan staff

Limit women, hurt their children

Like women the world over, Afghan women are filled with intelligence, creativity and vast potential. Yet for years now, Afghanistan has been considered the

“worst place to be a woman.”

Years of conflict and drought, the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, a major political shift and the withdrawal of Western support have combined to create a dismal reality for most women.

“Now I don’t know what to do,” one 30-year-old, educated professional

told a Canadian journalist recently. With 11 people to provide for by herself, she was asked to leave her job after the August 2021 regime change.

Most widowed Afghan women cannot inherit their husband’s land or return to their family of origin. The World Vision Shelter Project has been helping build small houses for women-led families. Photo: World Vision Afghanistan

Lack of women’s power in government

Most widowed Afghan women cannot inherit their husband’s land or return to their family of origin. The World Vision Shelter Project has been helping build small houses for women-led families. Photo: World Vision Afghanistan

Lack of women’s power in government

To fully represent women’s needs and rights – and nurture their immense potential – a country’s government needs female members and representation of women’s issues.

Over the past 20 years Afghanistan had made progress in that direction. By 2020,

20 per cent of Afghan civil servants were women, some in senior management levels. Also, 27 per cent of Afghan

members of parliament were women.

There was also a Women’s Affairs Ministry, which no longer exists. In September 2021, the

de facto authority replaced it with a

“Ministry for Preaching and Guidance and the Propagation of Virtue and the Prevention of Vice.”

Photo: World Vision Afghanistan

Photo: World Vision Afghanistan

Without a women’s ministry, or female government representation, many fear the rights of Afghan’s women won’t be protected, or their most basic needs for fulfilled.

These include access to – as well as the training of and employment of – female lawyers, teachers, doctors (including gynecologists) who are sensitive to the needs and rights of women and girls.

Healthcare beyond reach for many

For two decades, Afghanistan has

depended on international donor support to fund services such as health care. Even then, delivery of such services for women was

far below international standards.

Now, Afghan women and families face new challenges with respect to health care. There is a

ban on women travelling more than 72 kilometres being offered a ride, unless they have a male guardian with them.

This hits women and children in remote regions particularly hard. Most husbands, father and brothers are consumed with the daily task of finding food for their families, in a country dealing with economic collapse.

In 2020, 74 per cent of Afghans lived in rural or remote regions. For a man, forfeiting a day’s income to escort family members to the clinic can mean not feeding your family that day. Photo: World Vision Afghanistan

Legal system in flux

In 2020, 74 per cent of Afghans lived in rural or remote regions. For a man, forfeiting a day’s income to escort family members to the clinic can mean not feeding your family that day. Photo: World Vision Afghanistan

Legal system in flux

Afghanistan’s entire legal system is in flux, raising questions around women’s freedoms.

Over the past two decades, new or amended laws had offered hope and help for women. A 2009 law had been showing promise to reduce gender-based violence.

Legal aid clinics had sprung up, offering free or affordable representation to women in crisis. Women had become qualified – and were practicing – as lawyers and judges.

Quality of life for women and girls improves when they are respected. When they and their families gain access to improved economic and educational opportunities, both the present and the future become brighter.

Humanitarian response in Afghanistan: what is needed?

In January 2022, the UN and its partners announced a massive initiative to raise

$4.4 billion in funds for the response in Afghanistan for 2022. It’s the largest-ever appeal for a single country.

That same month, after months of assessment work, the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs released its humanitarian response plan for Afghanistan.

This plan describes what is happening in Afghanistan, identifies needs and target groups, and proposes response tactics. Here are some of the highlights:

- 24.4 million Afghans are in dire need.

- The humanitarian plan would reach 22.1 million people, meeting the most urgent needs of all.

- 21 per cent of the target population (to receive humanitarian assistance) are women and 54 per cent, children.

- 8.3 per cent of the target population live with a severe disability.

Families scrambled to help injured children, in the aftermath of a January 2022 earthquake which destroyed more than 1,000 homes. Photo: World Vision Afghanistan

Families scrambled to help injured children, in the aftermath of a January 2022 earthquake which destroyed more than 1,000 homes. Photo: World Vision Afghanistan

The proposed plan calls for humanitarian partners to work closely together, to prevent a broader collapse of basic services in Afghanistan. (Such a breakdown would further increase humanitarian needs).

Priority sectors for the plan include

food security and agriculture, health, protection of children and women, clean water and sanitation,

humanitarian shelter, nutrition and education.

Struggles facing humanitarian workers

On the ground in Afghanistan, humanitarians continue to assess and analyze rapidly growing needs, to ensure programs reach the most vulnerable of all.

Tragically, the areas in greatest need are often the hardest to reach, due to their remote locations. Major challenges persist for those delivering humanitarian assistance. Here are some examples:

- Factors such as deteriorating infrastructure severely hamper travel and communication.

- Ongoing violence in various pockets of the country, combined with the challenges of accessing remote areas during winter months.

- COVID-19 is still very much present, much harder to prevent with lack of health care education and supplies, as well as lack of clean water.

- Unpredictable natural threats like earthquakes and the relentless impact of climate change continue.

What is World Vision doing in Afghanistan?

For 20 years, World Vision Afghanistan has worked to address massive humanitarian needs in their country. They are committed to staying and delivering now.

Photo: World Vision Afghanistan

Photo: World Vision Afghanistan

Within World Vision Afghanistan, most of our more than 400 courageous staff members are themselves Afghans. Our teams are highly experienced in the practicalities of delivering assistance under immensely challenging circumstances.

Our staff work in several of Afghanistan’s Western areas. As part of this latest response, World Vision Afghanistan had reached nearly 450,000 girls, boys, women and men by March 2022. The work continue strong.

In these regions, we focus mainly on food security, health and nutrition, water and sanitation, and child protection. Here are a few examples of our work in the first six months (September 2021 – March 2022):

Health care

- Providing 31,000 people with primary health-care services, including screening for malnutrition for 7,200 young children.

- Caring for 2,340 children with acute malnutrition, restoring girls and boys to health.

- Providing 21 mobile health and nutrition teams to reach remote communities.

- Supporting 12 family “health houses,” places where community members can receive basic health and nutrition services.

Vaccinating 1,140 babies and providing

mental health and psychosocial counselling to 1,060 people.

Food security

- Providing cash-assistance and livelihood recovery options, so families could feed their children.

- Training people from 2,380 households with the skills to establish and maintain kitchen gardens.

- Distributing toolkits and seeds in March, in time for the spring planting.

Afghanistan is filled with girls and boys with boundless potential. They need and deserve every help we can give them. World Vision offices around the world (except in Canada) are raising funds for programs in Afghanistan.

Why people in Canada can’t donate for Afghanistan – for now

Right now, people here in Canada aren’t able to donate to the global relief effort in Afghanistan – although they know and care about the crisis.

Groups like World Vision Canada cannot raise funds specifically for programs in Afghanistan. We can’t help the Afghan people in the way we would like. Our Criminal Code makes it impossible.

Humanitarian imperative vs. Criminal Code

The Taliban is an entity which appears on many governments' list of terrorist entities. Most countries, including Canada, have rules in place to prevent money from flowing to these organization.

In Canada, the anti-terror legislation is very tight and provides no exemption for life-saving humanitarian work. The law was written to prevent funds – knowingly or unknowingly – from ending up in the hands of terrorist entities.

A solution must be found

World Vision Afghanistan has world-class checks and balances in place, to ensure international assistance funds are not diverted from the purpose for which they were intended.

Still, any organization operating in Afghanistan is required to pay taxes on staff salaries, rent and other basics. Right now, those tax revenues would go to the de facto authority.

A solution must be found. Other countries have found innovative ways to allow humanitarian aid to flow. Canada must too.

“In Afghanistan’s time of deepest need, Canadians want to help,” says Michael Messenger, president of World Vision Canada. “Our government needs to do everything it can to allow humanitarian aid to flow.”